Climbing on the Third Rock...

Many words can describe the wonderful activity of rock climbing—elegant, powerful, rewarding and, sometimes, frustrating. While there may be nothing more natural and intuitive than climbing (just watch how children climb around on everything in sight!), rock climbing is indeed a complex activity with demands unique from those of living and playing in the everyday, horizontal world.

Performing in the vertical plane requires physical capabilities such as strength, power, and endurance. It also demands the development of technical skills such as balance and economic movement while gripping and stepping in an infinite variety of ways, positions and angles. Most important, the inherent stress of climbing away from the safety of the ground requires acute control of your thoughts, focus, anxiety and fears. In aggregate, the above factors dovetail into what may be one of the more complex sporting activities on this third rock from the sun.

Performing in the vertical plane requires physical capabilities such as strength, power, and endurance. It also demands the development of technical skills such as balance and economic movement while gripping and stepping in an infinite variety of ways, positions and angles. Most important, the inherent stress of climbing away from the safety of the ground requires acute control of your thoughts, focus, anxiety and fears. In aggregate, the above factors dovetail into what may be one of the more complex sporting activities on this third rock from the sun.

In this first blog entry I will provide a primer on my philosophy of training for climbing. I’ve spend nearly three decades “researching” the subject by means of my thousands of successful climbs (and many failures), hundreds of hours per year spent training and working with other climbers of all ability levels, and countless days spent studying the subjects of sports psychology and exercise physiology. In addition, I’ve been blessed to talk training and climb with a diverse group of top climbers from Wolfgang Güllich to Lynn Hill to John Gill. Each day of my 28 years as a climber has revealed new distinctions on climbing performance as well as invaluable lessons for effective living. Let’s take a look at one such distinction.

The first step to elevating performance (in anything) is simply to “know thyself.” You can not progress beyond your current state with the same thoughts and actions that brought you here. Therefore, only through constant self-evaluation will you unlock the “secrets” to incremental improvement. For instance, you must actively discern what works from what does not work, as well as be able to recognize what you need to learn versus what must be unlearned. Often the key elements are not obvious or clear, but you must accept that life is subtle and only through improving on the little things will you succeed in the big things.

In climbing, the process of improvement begins with getting to know your patterns at the crags, when training, and in your everyday life. You must become aware of your climbing-related strengths and weaknesses in each area of the performance triad—technical, mental, and physical—and learn to leverage your strengths and improve upon the weaknesses. To this end, your prime directive must be to train intelligently—that is, to engage in training activities that best address your weaknesses, while not getting drawn into the trap of training as others do.

Thus, I hope this blog leads you to more effective ways of training and stretches your imagination as to what is possible in your life. I will challenge you with new ways of thinking just as I’ll teach you new training strategies. The path to higher performance and uncommon success is never obvious—it’s discovered only by those who embrace a more thoughtful and balanced approach. It’s my goal to help show you the way.

As a final distinction, consider that the act of climbing is an intimate dance between you and the rock; a dance in which you always lead. Recognize then, that climbing performance evolves from the inside out, and that you only trip and fall when you blow a move. Goethe wrote, “Nature understands no jesting; she is always true, always serious, always severe; she is always right, and the errors and faults are always those of man. The man incapable of appreciating her, she despises; and only to the apt, the pure, and the true, does she resign herself and reveal her secrets.” From this perspective it becomes obvious that we must sharpen our self-awareness and always look inside ourselves to identify what’s holding us back. The common mode of looking outward for the cause of failure (or to place blame) is a loser’s game.

I look forward to providing more insight into training for climbing and human performance in the weeks to come. Until my next post, I wish you success and happiness as you climb through this world of wonder. Be safe, and have fun!

I look forward to providing more insight into training for climbing and human performance in the weeks to come. Until my next post, I wish you success and happiness as you climb through this world of wonder. Be safe, and have fun!

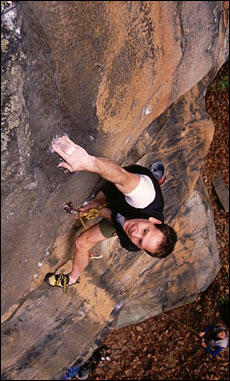

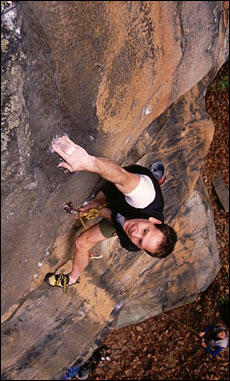

Photo (above): Eric Hörst on the first ascent of Logotherapy (5.13a/b), New River Gorge, WV. Courtesy of Eric McCallister.

Check out the best selling book at Training4Climbing.com.

Performing in the vertical plane requires physical capabilities such as strength, power, and endurance. It also demands the development of technical skills such as balance and economic movement while gripping and stepping in an infinite variety of ways, positions and angles. Most important, the inherent stress of climbing away from the safety of the ground requires acute control of your thoughts, focus, anxiety and fears. In aggregate, the above factors dovetail into what may be one of the more complex sporting activities on this third rock from the sun.

Performing in the vertical plane requires physical capabilities such as strength, power, and endurance. It also demands the development of technical skills such as balance and economic movement while gripping and stepping in an infinite variety of ways, positions and angles. Most important, the inherent stress of climbing away from the safety of the ground requires acute control of your thoughts, focus, anxiety and fears. In aggregate, the above factors dovetail into what may be one of the more complex sporting activities on this third rock from the sun.In this first blog entry I will provide a primer on my philosophy of training for climbing. I’ve spend nearly three decades “researching” the subject by means of my thousands of successful climbs (and many failures), hundreds of hours per year spent training and working with other climbers of all ability levels, and countless days spent studying the subjects of sports psychology and exercise physiology. In addition, I’ve been blessed to talk training and climb with a diverse group of top climbers from Wolfgang Güllich to Lynn Hill to John Gill. Each day of my 28 years as a climber has revealed new distinctions on climbing performance as well as invaluable lessons for effective living. Let’s take a look at one such distinction.

The first step to elevating performance (in anything) is simply to “know thyself.” You can not progress beyond your current state with the same thoughts and actions that brought you here. Therefore, only through constant self-evaluation will you unlock the “secrets” to incremental improvement. For instance, you must actively discern what works from what does not work, as well as be able to recognize what you need to learn versus what must be unlearned. Often the key elements are not obvious or clear, but you must accept that life is subtle and only through improving on the little things will you succeed in the big things.

In climbing, the process of improvement begins with getting to know your patterns at the crags, when training, and in your everyday life. You must become aware of your climbing-related strengths and weaknesses in each area of the performance triad—technical, mental, and physical—and learn to leverage your strengths and improve upon the weaknesses. To this end, your prime directive must be to train intelligently—that is, to engage in training activities that best address your weaknesses, while not getting drawn into the trap of training as others do.

Thus, I hope this blog leads you to more effective ways of training and stretches your imagination as to what is possible in your life. I will challenge you with new ways of thinking just as I’ll teach you new training strategies. The path to higher performance and uncommon success is never obvious—it’s discovered only by those who embrace a more thoughtful and balanced approach. It’s my goal to help show you the way.

As a final distinction, consider that the act of climbing is an intimate dance between you and the rock; a dance in which you always lead. Recognize then, that climbing performance evolves from the inside out, and that you only trip and fall when you blow a move. Goethe wrote, “Nature understands no jesting; she is always true, always serious, always severe; she is always right, and the errors and faults are always those of man. The man incapable of appreciating her, she despises; and only to the apt, the pure, and the true, does she resign herself and reveal her secrets.” From this perspective it becomes obvious that we must sharpen our self-awareness and always look inside ourselves to identify what’s holding us back. The common mode of looking outward for the cause of failure (or to place blame) is a loser’s game.

I look forward to providing more insight into training for climbing and human performance in the weeks to come. Until my next post, I wish you success and happiness as you climb through this world of wonder. Be safe, and have fun!

I look forward to providing more insight into training for climbing and human performance in the weeks to come. Until my next post, I wish you success and happiness as you climb through this world of wonder. Be safe, and have fun!Photo (above): Eric Hörst on the first ascent of Logotherapy (5.13a/b), New River Gorge, WV. Courtesy of Eric McCallister.

Check out the best selling book at Training4Climbing.com.

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed

4 Comments:

Hi Eric,

I have been climbing for several years. During which I have climbed all sorts of climbs(from Trad to Sport) and in all sorts of conditions. I feel I am pretty proficient technically speaking, however when it comes to leading I can never lead as hard of a climb as I can follow. This is primarily due to fear of taking a big fall (thus I hesitate when I need to execute). Do you have any recommendations on how to push through this mental roadblock.

Thanks!

Hey Todd,

What you describe is common, and it can be worked through with a combination of reason and old fashion guts. When you get scared, analyze whether the fear is legitimate or not--can you reason it away? On sport routes (i.e. safe climbs), sometimes you just need to suck it up and push your boundaries until you fall (or send!). Here's a link to provide a few more strategies. Good luck, and be safe! --EH

Vielen Dank Eric.

Tschus,

Todd

Hey Eric,

Your words are a demise in thoughts,....very apreciated..

To me and my mates, i'm just less like to climber for 1 years and not even regular, but my friends down here are climbing for years but can't break the improovment barrier.like climbing at 5.13 or 5.14..this is realy what we want...

its not only about that mental or something we realy want some special exercices...

danke eric, ich hoffe wir hoeren von dir.

viele gruese aus dem iran..

M.K

Post a Comment

<< Home